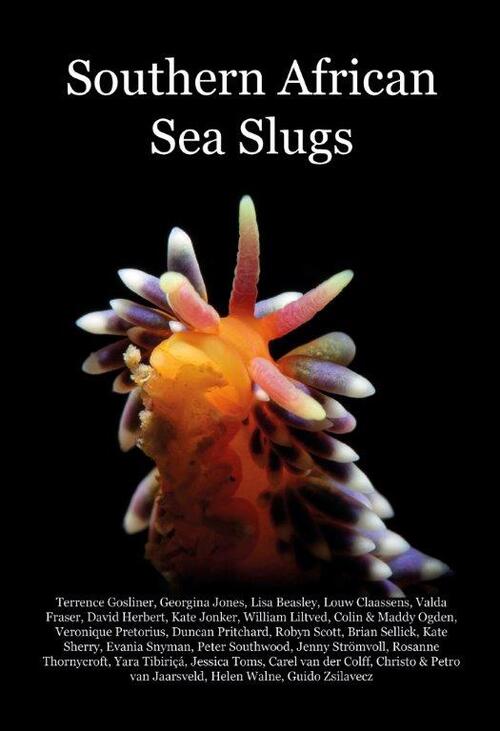

Southern African Sea slugs

TEXT By GEORGINA JONES

The story of the making of ‘Southern African Sea Slugs’ began in a California rockpool when Terry Gosliner, then 15, saw his first nudibranch. He was hooked and set out on a career in invertebrate zoology, particularly sea slugs. So dedicated has he been that he has, out of the around 3,000 scientifically described sea slug species globally, himself described 1,000 species. His first post was as head of malacology (the study of snails and slugs) at Iziko (then the South African Museum) in Cape Town, and his first published book, in 1987, was a field guide to the sea slugs of Southern Africa.

Fast forward to 2018, when a project called SeaKeys was underway. It aimed to unlock a basic biological understanding of South African marine species, and part of that included getting world experts to come out to South Africa and help identify species and share their knowledge with locals. Terry was, of course, asked to give a nudibranch workshop. His plan for the workshop was to invite area specialists, whether divers, underwater photographers, or academics, from around the region. At the end of the seminar, he explained that he wanted to use all the group's observations of the size and behaviour of the sea slug species in their areas to produce an update of his 1987 book.

This approach to making a field guide makes its contents much more wide-ranging and considerably more accurate, particularly in terms of distribution, than a guide produced by the observations of only a few people. And so the data collection began. It involved the observations of 80 photographers and thousands of photographs, all of which had to be identified, arranged into species, and then described. It was a rather major undertaking.

The guide includes all 868 sea slugs from around southern Africa. Several never-before-known species are shown, along with previously unknown egg ribbons (sea slugs

The story of the making of ‘Southern African Sea Slugs’ began in a California rockpool when Terry Gosliner, then 15, saw his first nudibranch. He was hooked and set out on a career in invertebrate zoology, particularly sea slugs. So dedicated has he been that he has, out of the around 3,000 scientifically described sea slug species globally, himself described 1,000 species. His first post was as head of malacology (the study of snails and slugs) at Iziko (then the South African Museum) in Cape Town, and his first published book, in 1987, was a field guide to the sea slugs of Southern Africa.

Fast forward to 2018, when a project called SeaKeys was underway. It aimed to unlock a basic biological understanding of South African marine species, and part of that included getting world experts to come out to South Africa and help identify species and share their knowledge with locals. Terry was, of course, asked to give a nudibranch workshop. His plan for the workshop was to invite area specialists, whether divers, underwater photographers, or academics, from around the region. At the end of the seminar, he explained that he wanted to use all the group's observations of the size and behaviour of the sea slug species in their areas to produce an update of his 1987 book.

This approach to making a field guide makes its contents much more wide-ranging and considerably more accurate, particularly in terms of distribution, than a guide produced by the observations of only a few people. And so the data collection began. It involved the observations of 80 photographers and thousands of photographs, all of which had to be identified, arranged into species, and then described. It was a rather major undertaking.

The guide includes all 868 sea slugs from around southern Africa. Several never-before-known species are shown, along with previously unknown egg ribbons (sea slugs

produce species-specific egg ribbons that can be useful in distinguishing between species). One species, photographed by a volunteer at the Two Oceans Aquarium, had not been seen since it was scientifically described in 1927. Other more unfortunate observations provided evidence of what eats nudibranchs: they were photographed being eaten by sea spiders, other sea slugs and an anemone. Dedicated beachcombers and rock poolers, particularly in the Eastern Cape, provided observations of range extensions.

The guide has been formatted with ease of identification in mind: the inside front cover has a series of line drawings showing different body shapes with relevant page numbers. The whole book is colour-coded according to which group of sea slugs is being covered, the colours coming from an evolutionary schematic that shows the relationships between the groups. As well as nudibranchs, the groups include bubble snails, sidegill slugs, umbrella snails, sea hares, sea butterflies and sea angels, headshield slugs, sap-sucking slugs and air-breathing sea slugs. A motley crew! But in the guide, each group has been assigned a colour marked on the header and down the side of each page, making it easy to find a particular group. Within the nudibranchs, the biggest group, there are also colour codes for each biological family.

Each major group begins with an overall description of the group characteristics, and each species is listed with a quick-find distribution icon showing which coast it has been seen on -- blue for the West Coast, green for the South and red for the warmer East Coast. The depth of the icon colour indicates the depth at which the species has been seen.

Since the guide, though written using current academic classification, is intended for recreational users, each species has been given a common name. In some cases, the names existed; in others, they were formulated according to species diagnostics.

The guide has been formatted with ease of identification in mind: the inside front cover has a series of line drawings showing different body shapes with relevant page numbers. The whole book is colour-coded according to which group of sea slugs is being covered, the colours coming from an evolutionary schematic that shows the relationships between the groups. As well as nudibranchs, the groups include bubble snails, sidegill slugs, umbrella snails, sea hares, sea butterflies and sea angels, headshield slugs, sap-sucking slugs and air-breathing sea slugs. A motley crew! But in the guide, each group has been assigned a colour marked on the header and down the side of each page, making it easy to find a particular group. Within the nudibranchs, the biggest group, there are also colour codes for each biological family.

Each major group begins with an overall description of the group characteristics, and each species is listed with a quick-find distribution icon showing which coast it has been seen on -- blue for the West Coast, green for the South and red for the warmer East Coast. The depth of the icon colour indicates the depth at which the species has been seen.

Since the guide, though written using current academic classification, is intended for recreational users, each species has been given a common name. In some cases, the names existed; in others, they were formulated according to species diagnostics.

The scientific name is shown alongside thecommon name for scientific use and ease of comparison with other guides.

Images for each species show as many variants as are known for the species from the region. In cases where the photos submitted were too problematic to be printed, they have been reproduced in watercolour. Where known, the guide details what environment the animals prefer, what they eat, what eats them and what their egg ribbons look like.

There's also a section at the end of the book for egg ribbons, arranged by egg ribbon shape. In the species descriptions, a final entry details anything of interest about the species that may be known: who the species was named for or what it is called in texts and any other snippets.

Perhaps it will inspire a new generation of rock poolers and underwater enthusiasts to discover more about these fascinating animals.

Images for each species show as many variants as are known for the species from the region. In cases where the photos submitted were too problematic to be printed, they have been reproduced in watercolour. Where known, the guide details what environment the animals prefer, what they eat, what eats them and what their egg ribbons look like.

There's also a section at the end of the book for egg ribbons, arranged by egg ribbon shape. In the species descriptions, a final entry details anything of interest about the species that may be known: who the species was named for or what it is called in texts and any other snippets.

Perhaps it will inspire a new generation of rock poolers and underwater enthusiasts to discover more about these fascinating animals.

Posted in Alert Diver Southern Africa, Press Release, Research, Underwater Conservation

Posted in Nudibranchs, Sea slugs, Underwater critters, Guidebook, Georgina Jones

Posted in Nudibranchs, Sea slugs, Underwater critters, Guidebook, Georgina Jones

Categories

2025

2024

February

March

April

May

October

My name is Rosanne… DAN was there for me?My name is Pam… DAN was there for me?My name is Nadia… DAN was there for me?My name is Morgan… DAN was there for me?My name is Mark… DAN was there for me?My name is Julika… DAN was there for me?My name is James Lewis… DAN was there for me?My name is Jack… DAN was there for me?My name is Mrs. Du Toit… DAN was there for me?My name is Sean… DAN was there for me?My name is Clayton… DAN was there for me?My name is Claire… DAN was there for me?My name is Lauren… DAN was there for me?My name is Amos… DAN was there for me?My name is Kelly… DAN was there for me?Get to Know DAN Instructor: Mauro JijeGet to know DAN Instructor: Sinda da GraçaGet to know DAN Instructor: JP BarnardGet to know DAN instructor: Gregory DriesselGet to know DAN instructor Trainer: Christo van JaarsveldGet to Know DAN Instructor: Beto Vambiane

November

Get to know DAN Instructor: Dylan BowlesGet to know DAN instructor: Ryan CapazorioGet to know DAN Instructor: Tyrone LubbeGet to know DAN Instructor: Caitlyn MonahanScience Saves SharksSafety AngelsDiving Anilao with Adam SokolskiUnderstanding Dive Equipment RegulationsDiving With A PFOUnderwater NavigationFinding My PassionDiving Deep with DSLRDebunking Freediving MythsImmersion Pulmonary OedemaSwimmer's EarMEMBER PROFILE: RAY DALIOAdventure Auntie: Yvette OosthuizenClean Our OceansWhat to Look for in a Dive Boat

2023

January

March

Terrific Freedive ModeKaboom!....The Big Oxygen Safety IssueScuba Nudi ClothingThe Benefits of Being BaldDive into Freedive InstructionCape Marine Research and Diver DevelopmentThe Inhaca Ocean Alliance.“LIGHTS, Film, Action!”Demo DiversSpecial Forces DiverWhat Dive Computers Don\'t Know | PART 2Toughing It Out Is Dangerous

April