Lost Divers | Missed Opportunity

TEXT by Dr CLEEVE ROBERTSON (MBCHB FEMSSA)

Some time ago, I gave a talk at a DAN Workshop at False Bay Underwater Club on lost divers, perhaps naively thinking that these occurrences are rare. Still, in the recent past, the last few weeks, there have been several lost diver incidents, mainly along the East Coast.

We spend hours looking for lost divers, meaning that if you get lost, you will be in the water for a long time. I will never forget the story of my mate who, during an ascent on Deco, had to release a jammed buoy line, and by the time they surfaced, the boat was nowhere to be seen, and they drifted through the night somewhere off Zanzibar until they were found the next day. Or my trip to Bassas da India, almost thirty years ago, when the boat guy, not a diver and with no diving experience, overshot the dive group and ended up two kilometres down the reef.

Fortunately, we could swim to the submerged reef and walk backwards until we could swim to our yacht. Then on my last trip to Zanzibar, I surfaced with the DM in quite a hostile choppy

sea, off Mnemba Island, only to find the boat was attending to the snorkelers closer in, about a kilometre away. We waited over thirty minutes before waving down another boat and getting a lift back to the ‘mother ship’!

On the positive side, in 2019, I took an adventure diving trip off Agulhas and was dropped into 30m of water 12 nautical miles from the Southern Tip of Africa. When we surfaced in 2- 3m swells, choppy sea and a strong Westerly, the skipper was right on top of us.

It goes without saying that prevention is better than a kick in the pants, and there’s a definite psychology involved in making sure that divers never get lost. I’ve learned in Emergency Services that systems involve team dynamics and that a team’s collective, coordinated action ensures safety. Everyone knows about the Swiss Cheese Model and the Domino Theory of Accident evolution, and the challenge is to close those holes and keep the dominoes upright by ensuring that each team member does their job.

Although Maritime Law places the responsibility for safety on the boat skipper, we’ve learned, from recent litigation, that responsibility and accountability accrues to everyone in the dive group from the dive business, operator, instructor, divemaster, skipper and even the dive buddy. Each one has a unique role in a sequence towards safety.

Safety is a culture, and although checklists, operating procedures and tick boxes may be useful, people's ownership and commitment to safety make the most significant difference. Reputations make an industry, and financial sustainability individually and collectively depends on a reputation for safety.

So lost divers start with the leadership in the business, the quality of training, the experience of operators, the responsibility demonstrated, and the diligence to elements that guarantee safety.

I once had an attorney greet me after a talk I had given at the Royal Cape Yacht Club. He had been one of my dive trainees thirty years before, and he remembers that one of the most important lessons I had taught him was that sometimes the conditions were not safe to dive. He recalled that one lesson, not safe! (he was referring to a howling offshore South Easterly wind on a shore dive)

The obvious immediate preventative actions related to each dive concerning lost divers include weather assessments, dive briefings, communication between skipper and divemaster, group sizing and the use of location aids.

Each operator should have limits, wind, swell, visibility, and current, in terms of which a dive can be safely conducted. One can use a simple hazard identification and risk assessment tool to compute the combined risk, which assists decision-making. Swell and sea conditions are significant components of being able to locate divers on the surface. Searchers use terms like

Probability of Area (POA) which relates mainly to current, and Probability of Detection (POD) which relates to the environmental and sea conditions. If you don’t know, don’t go!

Dive briefing must include information that facilitates the group's understanding of the dive and all the safety aspects that prevent diver separation and loss. Maintaining the relatively appropriate diver proximity for visibility is very important, and divers should easily be able to identify the divemaster/lead in their group. Night dives present unique challenges, but a flashing underwater strobe, for example, can differentiate the leader from the rest with cyalume sticks.

Brief for belief!

The divemaster, as is standard practice, should drag a buoy that is visible to the skipper on the boat at all times. This may be difficult on deep dives with a strong current. I always insist that every diver has a reel and buoy because any one of the group can become separated. Recent incidents have indicated that the wind often knocks over the tube buoy that divers deploy, so it’s essential to keep it under tension and vertical in the water if you are separated from the boat. These physical detection aids and practices are probably the most effective actions to ensure detection.

Be for Buoys!

Sound devices attached to the BC power feed may be helpful but are unlikely to be universal.

I’m often asked about VHF radios, AIS Beacons, Personal Locator Beacons (PLBs) and cellphones as ways of sending a location from a lost diver. The answer is that the communication loop needs to be closed, which means the device has to be part of a system that someone will respond to. It’s useless activating a device if nobody detects or receives the message and activates a response. AIS beacons set off an alarm on the boat they are closest to, but the skipper must recognise the alarm. Most skippers have never heard one go off! Once recognised, finding the person is easy because the missing person is GIS located

Some time ago, I gave a talk at a DAN Workshop at False Bay Underwater Club on lost divers, perhaps naively thinking that these occurrences are rare. Still, in the recent past, the last few weeks, there have been several lost diver incidents, mainly along the East Coast.

We spend hours looking for lost divers, meaning that if you get lost, you will be in the water for a long time. I will never forget the story of my mate who, during an ascent on Deco, had to release a jammed buoy line, and by the time they surfaced, the boat was nowhere to be seen, and they drifted through the night somewhere off Zanzibar until they were found the next day. Or my trip to Bassas da India, almost thirty years ago, when the boat guy, not a diver and with no diving experience, overshot the dive group and ended up two kilometres down the reef.

Fortunately, we could swim to the submerged reef and walk backwards until we could swim to our yacht. Then on my last trip to Zanzibar, I surfaced with the DM in quite a hostile choppy

sea, off Mnemba Island, only to find the boat was attending to the snorkelers closer in, about a kilometre away. We waited over thirty minutes before waving down another boat and getting a lift back to the ‘mother ship’!

On the positive side, in 2019, I took an adventure diving trip off Agulhas and was dropped into 30m of water 12 nautical miles from the Southern Tip of Africa. When we surfaced in 2- 3m swells, choppy sea and a strong Westerly, the skipper was right on top of us.

It goes without saying that prevention is better than a kick in the pants, and there’s a definite psychology involved in making sure that divers never get lost. I’ve learned in Emergency Services that systems involve team dynamics and that a team’s collective, coordinated action ensures safety. Everyone knows about the Swiss Cheese Model and the Domino Theory of Accident evolution, and the challenge is to close those holes and keep the dominoes upright by ensuring that each team member does their job.

Although Maritime Law places the responsibility for safety on the boat skipper, we’ve learned, from recent litigation, that responsibility and accountability accrues to everyone in the dive group from the dive business, operator, instructor, divemaster, skipper and even the dive buddy. Each one has a unique role in a sequence towards safety.

Safety is a culture, and although checklists, operating procedures and tick boxes may be useful, people's ownership and commitment to safety make the most significant difference. Reputations make an industry, and financial sustainability individually and collectively depends on a reputation for safety.

So lost divers start with the leadership in the business, the quality of training, the experience of operators, the responsibility demonstrated, and the diligence to elements that guarantee safety.

I once had an attorney greet me after a talk I had given at the Royal Cape Yacht Club. He had been one of my dive trainees thirty years before, and he remembers that one of the most important lessons I had taught him was that sometimes the conditions were not safe to dive. He recalled that one lesson, not safe! (he was referring to a howling offshore South Easterly wind on a shore dive)

The obvious immediate preventative actions related to each dive concerning lost divers include weather assessments, dive briefings, communication between skipper and divemaster, group sizing and the use of location aids.

Each operator should have limits, wind, swell, visibility, and current, in terms of which a dive can be safely conducted. One can use a simple hazard identification and risk assessment tool to compute the combined risk, which assists decision-making. Swell and sea conditions are significant components of being able to locate divers on the surface. Searchers use terms like

Probability of Area (POA) which relates mainly to current, and Probability of Detection (POD) which relates to the environmental and sea conditions. If you don’t know, don’t go!

Dive briefing must include information that facilitates the group's understanding of the dive and all the safety aspects that prevent diver separation and loss. Maintaining the relatively appropriate diver proximity for visibility is very important, and divers should easily be able to identify the divemaster/lead in their group. Night dives present unique challenges, but a flashing underwater strobe, for example, can differentiate the leader from the rest with cyalume sticks.

Brief for belief!

The divemaster, as is standard practice, should drag a buoy that is visible to the skipper on the boat at all times. This may be difficult on deep dives with a strong current. I always insist that every diver has a reel and buoy because any one of the group can become separated. Recent incidents have indicated that the wind often knocks over the tube buoy that divers deploy, so it’s essential to keep it under tension and vertical in the water if you are separated from the boat. These physical detection aids and practices are probably the most effective actions to ensure detection.

Be for Buoys!

Sound devices attached to the BC power feed may be helpful but are unlikely to be universal.

I’m often asked about VHF radios, AIS Beacons, Personal Locator Beacons (PLBs) and cellphones as ways of sending a location from a lost diver. The answer is that the communication loop needs to be closed, which means the device has to be part of a system that someone will respond to. It’s useless activating a device if nobody detects or receives the message and activates a response. AIS beacons set off an alarm on the boat they are closest to, but the skipper must recognise the alarm. Most skippers have never heard one go off! Once recognised, finding the person is easy because the missing person is GIS located

on the vessel plotter. These AIS PLBs would need to be waterproofed for pressure to be used by divers.

Short Range VHF radios designed for diving use are also on the market, but again if nobody is listening or monitoring, the message or distress goes nowhere. We haven’t created a national network and structure to detect and respond to these devices.

The NSRI manages a very successful cellphone App called SafeTRX, which requires that the cellphone be dived in a waterproof pouch. It also needs the cellphone to be within network range. Our experience with the Surfski community has demonstrated that it works well even far out to sea, but there’s no guarantee.

Smoke flares are another possibility, but they are expensive, not universal and difficult to waterproof.

SO, IN SUMMARY.

Owning responsibility and accountability for safety is non-negotiable.

A safety culture is a must.

Planning and preparation to prevent lost divers are essential.

Team dynamics and cohesion are key. Create HIRAs to inform safe diving conditions.

Ensure dive group proximity and contact. Use practical detection aids, and buoys, collectively, and individually. Don’t depend on electronic communication devices unless you’ve tested the system.

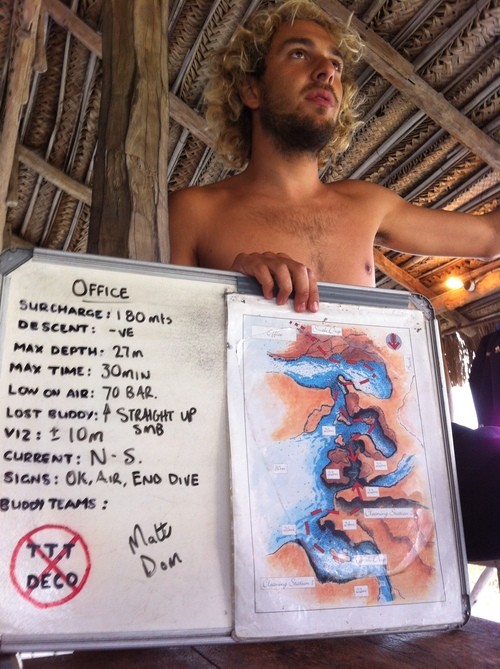

EXAMPLE DIVEMASTER BRIEFING ON LOST DIVER PROCEDURE

Lost diver briefing:

Avoiding getting lost in the first place:

4. Surface as quickly as is safe. Deploy your SMB and keep the line under tension to ensure maximum buoy height. Avoid your safety stop if safe to do so. Remember that during strong current drift dives and in rough conditions – the surface 5m of water moves much faster than the group at the bottom, and thus further away from the boat watching the buoy line. If you surface more than 50m from the buoy line, there is a good chance the boat won’t see you – so get to the surface quickly to reduce the chances of not being seen by the skipper.(

5. On surfacing – at about 5m depth – “purge” your regulator to make a plume of bubbles that is visible on the surface. This “warns” vessels that a diver is below and surfacing – to reduce the possibility of being run over, and alerts good skippers that divers are away from the group.

Short Range VHF radios designed for diving use are also on the market, but again if nobody is listening or monitoring, the message or distress goes nowhere. We haven’t created a national network and structure to detect and respond to these devices.

The NSRI manages a very successful cellphone App called SafeTRX, which requires that the cellphone be dived in a waterproof pouch. It also needs the cellphone to be within network range. Our experience with the Surfski community has demonstrated that it works well even far out to sea, but there’s no guarantee.

Smoke flares are another possibility, but they are expensive, not universal and difficult to waterproof.

SO, IN SUMMARY.

Owning responsibility and accountability for safety is non-negotiable.

A safety culture is a must.

Planning and preparation to prevent lost divers are essential.

Team dynamics and cohesion are key. Create HIRAs to inform safe diving conditions.

Ensure dive group proximity and contact. Use practical detection aids, and buoys, collectively, and individually. Don’t depend on electronic communication devices unless you’ve tested the system.

EXAMPLE DIVEMASTER BRIEFING ON LOST DIVER PROCEDURE

Lost diver briefing:

- Must be clearly and powerfully delivered – it's essential!

- Make sure your divers hear it, and understand it, i.e. make eye contact with them as you are delivering it to ensure comprehension.

Avoiding getting lost in the first place:

- Stay within sight of the buoy line & person holding the buoy line always (Descent, during the dive, on ascent)

- Don’t descend if you cannot see the line/person holding the line – you won’t find them underwater

How to know if you are lost: - If during the dive, you find yourself away from the buoy line/holder, ascend a metre or two, rotate and search for bubbles/bright colours to locate the buoy line/holder. But – take no more than five breaths doing this. If, after five breaths, you can’t see the buoy line/holder (irrespective of whether you are on your own or as part of a group), you are lost!

4. Surface as quickly as is safe. Deploy your SMB and keep the line under tension to ensure maximum buoy height. Avoid your safety stop if safe to do so. Remember that during strong current drift dives and in rough conditions – the surface 5m of water moves much faster than the group at the bottom, and thus further away from the boat watching the buoy line. If you surface more than 50m from the buoy line, there is a good chance the boat won’t see you – so get to the surface quickly to reduce the chances of not being seen by the skipper.(

5. On surfacing – at about 5m depth – “purge” your regulator to make a plume of bubbles that is visible on the surface. This “warns” vessels that a diver is below and surfacing – to reduce the possibility of being run over, and alerts good skippers that divers are away from the group.

6. On the surface, unless you see that the boat is aware of you, inflate your SMB as soon as possible, and hold it taut so it is vertical in the air (all divers should have one). If you don’t have one–useafintowaveintheair–toincrease your height of visibility by a vessel.

7. Use your whistle (sometimes on snorkel, sometimes on BCD, etc.) to attract attention.

8. If you are not picked up by a vessel in 10 min – consider self-rescue to the shore. Always stay together with your buddy/group – never separate! Together you add more visibility than a single person. Self-rescue (no matter how far offshore) is a mind game, so stay calm, keep focused, and maintain an economical pace that you can maintain for a few hours – slow but steady. Don’t tire yourself; the current will help.

9. Use any signalling/tracking device you may have but know how it works before you need to use it!

What to do if you are the DM and notice a lost diver/group of divers?:

10. A good DM constantly counts their divers to know that all are accounted for.

11. If you notice that one or more divers are missing, then essentially, it is the same procedure:

12.. Surface a few metres to search for bubbles/bright colours, etc. Take no more than five breaths doing so.

13. After five breaths, and no one is found, terminate the dive and get everybody to the surface as quickly and safely as possible.

Annoyed-off customers are better than lost divers never found; it’s not an option.

By explaining this consequence in the briefing – divers are more likely to ensure that they stay with the group.

14. Alert the skipper as soon as you break the surface – to check if the “lost divers” are on board. If not – the skipper can take a minute (no more) to do a quick circle around the group (before loading the divers but keeping the divers visible) to see if they can spot the lost divers. If none are found after 1 minute, then return to the group, and alert shore/base/other operators/other vessels/NSRI to begin a search/process.

15. The sooner the search begins – the smaller the search area. After an hour – the search area grows exponentially – especially in strong currents. Rather call out the NSRI and stand them down after 5 or 10 minutes than wait a few hours when search success becomes more difficult.

16. Once the not-lost divers are loaded, the vessel should stay on-site and search for as long as fuel allows. Relaying the following information as soon as possible is critical:

The exact time and location the lost divers were last seen.

Dive conditions – current strength (bottom/top) and direction. The more precise, the better (i.e. bearing of 190 degrees vs. Southerly current).

Details of the persons being searched for (gender/name/age/colour wetsuit, etc.).

17. The NSRI has sophisticated search tools, programmes & techniques, which depend on the data accuracy given. The earlier and more accurate – the better chances of a good outcome for the lost diver.

Tips for good skippers/vessel operators:

- Maintain visibility of the buoy line at all times.

- Good skippers also maintain visibility of bubbles (when not too deep/too rough) and “groups” of bubbles moving away from the buoy line so that despite divers' best efforts - the skipper doesn’t lose them.

- The ability to take landmarks (when visual) gives skippers a great spatial awareness of the reef and current strength and conditions. This skill has tended to be lost in the age of GPS but is valuable in knowing where divers are and are going.

- Be careful of relying on your senses when further offshore and out of sight of land – rather trust a compass / GPS for directions than your “feeling”.

- Vessels must have communication -whether cell phone or VHF radio. Communicating positions and the fact that an emergency has happened is very important. Operators that don’t have or do this endanger lives, the business and the industry.

- Skippers should “mentally practise” the various emergency procedures so that if and when they do happen, they are executed as effectively as possible. Rescue diver courses are also great practice for skippers – instructors should include them when possible.

Posted in Alert Diver Southern Africa, Dive Safety Tips

Posted in Dive safety, Lost divers, NSRI, Sea rescue, Dive safety briefing, Dive leaders, Dive Masters, Cleeve Robertson, Self Rescue, Signalling devices, SMB

Posted in Dive safety, Lost divers, NSRI, Sea rescue, Dive safety briefing, Dive leaders, Dive Masters, Cleeve Robertson, Self Rescue, Signalling devices, SMB

Categories

2025

2024

February

March

April

May

October

My name is Rosanne… DAN was there for me?My name is Pam… DAN was there for me?My name is Nadia… DAN was there for me?My name is Morgan… DAN was there for me?My name is Mark… DAN was there for me?My name is Julika… DAN was there for me?My name is James Lewis… DAN was there for me?My name is Jack… DAN was there for me?My name is Mrs. Du Toit… DAN was there for me?My name is Sean… DAN was there for me?My name is Clayton… DAN was there for me?My name is Claire… DAN was there for me?My name is Lauren… DAN was there for me?My name is Amos… DAN was there for me?My name is Kelly… DAN was there for me?Get to Know DAN Instructor: Mauro JijeGet to know DAN Instructor: Sinda da GraçaGet to know DAN Instructor: JP BarnardGet to know DAN instructor: Gregory DriesselGet to know DAN instructor Trainer: Christo van JaarsveldGet to Know DAN Instructor: Beto Vambiane

November

Get to know DAN Instructor: Dylan BowlesGet to know DAN instructor: Ryan CapazorioGet to know DAN Instructor: Tyrone LubbeGet to know DAN Instructor: Caitlyn MonahanScience Saves SharksSafety AngelsDiving Anilao with Adam SokolskiUnderstanding Dive Equipment RegulationsDiving With A PFOUnderwater NavigationFinding My PassionDiving Deep with DSLRDebunking Freediving MythsImmersion Pulmonary OedemaSwimmer's EarMEMBER PROFILE: RAY DALIOAdventure Auntie: Yvette OosthuizenClean Our OceansWhat to Look for in a Dive Boat

2023

January

March

Terrific Freedive ModeKaboom!....The Big Oxygen Safety IssueScuba Nudi ClothingThe Benefits of Being BaldDive into Freedive InstructionCape Marine Research and Diver DevelopmentThe Inhaca Ocean Alliance.“LIGHTS, Film, Action!”Demo DiversSpecial Forces DiverWhat Dive Computers Don\'t Know | PART 2Toughing It Out Is Dangerous

April