Going Up

CREDITS | Text and photos by Mike Bartick

Zooplankton’s daily vertical migration

Every night as the sun slips below the horizon, countless aquatic creatures begin migrating up from the deep in what is quite possibly the greatest show on Earth. Seeking nourishment in shallow water, zooplankton must risk a perilous journey upward, avoiding a gauntlet of predators while remaining in the safety of darkness and then returning to the deep before the next sunrise.

In 1817 French naturalist Georges Cuvier first described the diel vertical migration (DVM) of zooplankton. Diel comes from the Latin dies, meaning day; biologists use the term to refer to a period of 24 hours. This specific, cyclical migration behavior, however, is exclusive to zooplankton. While it is part of a daily cycle, the crucial movement occurs globally each night across a diverse number of taxonomic groups, including protozoans, worms, nudibranchs, krill, shrimp, tunicates, and some jellyfish, among others. Despite the movement of possibly billions of organisms, the occurrence has gone largely unnoticed by nearly everyone outside of the scientific community.

The distance this group of migrating minifauna traverses and why they migrate are some of nature’s greatest mysteries. As scientists have studied DVM over the years, they’ve discovered that while the migration alone is fascinating, it’s only a sneak peek at the entire story. DVM is a multifaceted event that involves plankton, fish, and other natural elements, with more clues as to why continually being revealed.

Zooplankton’s daily vertical migration

Every night as the sun slips below the horizon, countless aquatic creatures begin migrating up from the deep in what is quite possibly the greatest show on Earth. Seeking nourishment in shallow water, zooplankton must risk a perilous journey upward, avoiding a gauntlet of predators while remaining in the safety of darkness and then returning to the deep before the next sunrise.

In 1817 French naturalist Georges Cuvier first described the diel vertical migration (DVM) of zooplankton. Diel comes from the Latin dies, meaning day; biologists use the term to refer to a period of 24 hours. This specific, cyclical migration behavior, however, is exclusive to zooplankton. While it is part of a daily cycle, the crucial movement occurs globally each night across a diverse number of taxonomic groups, including protozoans, worms, nudibranchs, krill, shrimp, tunicates, and some jellyfish, among others. Despite the movement of possibly billions of organisms, the occurrence has gone largely unnoticed by nearly everyone outside of the scientific community.

The distance this group of migrating minifauna traverses and why they migrate are some of nature’s greatest mysteries. As scientists have studied DVM over the years, they’ve discovered that while the migration alone is fascinating, it’s only a sneak peek at the entire story. DVM is a multifaceted event that involves plankton, fish, and other natural elements, with more clues as to why continually being revealed.

The ocean has several primary zones determined by depth and how far sunlight penetrates the water. The sunlight or epipelagic zone is from the surface down to 656 feet, and it has enough light to support plants that rely on it. The twilight or mesopelagic zone, where light is minimal, reaches from the bottom of the sunlight zone down to 3,280 feet. Below that are the deepest and darkest zones: bathypelagic, abyssopelagic, and hadopelagic.

Like plants on land, phytoplankton in the epipelagic zone thrive on sunlight, consume carbon dioxide, and store the converted carbon. During this process, chlorophyll in the phytoplankton also respire oxygen back into Earth’s atmosphere, making them a significant contributor among marine plants, which provide more than half of the oxygen we breathe.

At the surface, the never-ending cycle of natural elements — including sunlight, wind, and ocean movement — churns the top layer of water, which can push the phytoplankton downward. Others will die near the surface and float down toward the ocean floor.

The upward-migrating, herbivorous zooplankton and their predators intersect with the phytoplankton at the surface and consume as much as they can. As the night slowly becomes morning, the zooplankton return to deeper, cooler, and denser water, where they expel much of their waste. These ways in which phytoplankton travel downward result in their carbon moving to the deep ocean. This sequence of movement and carbon conversion is called the biological carbon pump, which relocates about 10 gigatons of carbon every year. It is perhaps one of the most extensive ecological functions on the planet, ironically carried out by some of the smallest organisms.

Scientists employ deep-sea trawls to study the multitude of organisms and collect, sample, and document various life forms from different depths. The trawls have revealed much over the years, but they can provide only a snapshot of each zone trawled.

Advancing technologies in small, crewed submersibles that can withstand the intense pressures of the deep offer a different way to study plankton. These small subs enable scientists to conduct exploratory jaunts to the twilight zone and beyond, but life-support obligations limit their time at depth. While on these deep-sea expeditions, researchers can passively observe extraordinary, otherworldly life forms in their natural element or selectively collect them to study.

Like plants on land, phytoplankton in the epipelagic zone thrive on sunlight, consume carbon dioxide, and store the converted carbon. During this process, chlorophyll in the phytoplankton also respire oxygen back into Earth’s atmosphere, making them a significant contributor among marine plants, which provide more than half of the oxygen we breathe.

At the surface, the never-ending cycle of natural elements — including sunlight, wind, and ocean movement — churns the top layer of water, which can push the phytoplankton downward. Others will die near the surface and float down toward the ocean floor.

The upward-migrating, herbivorous zooplankton and their predators intersect with the phytoplankton at the surface and consume as much as they can. As the night slowly becomes morning, the zooplankton return to deeper, cooler, and denser water, where they expel much of their waste. These ways in which phytoplankton travel downward result in their carbon moving to the deep ocean. This sequence of movement and carbon conversion is called the biological carbon pump, which relocates about 10 gigatons of carbon every year. It is perhaps one of the most extensive ecological functions on the planet, ironically carried out by some of the smallest organisms.

Scientists employ deep-sea trawls to study the multitude of organisms and collect, sample, and document various life forms from different depths. The trawls have revealed much over the years, but they can provide only a snapshot of each zone trawled.

Advancing technologies in small, crewed submersibles that can withstand the intense pressures of the deep offer a different way to study plankton. These small subs enable scientists to conduct exploratory jaunts to the twilight zone and beyond, but life-support obligations limit their time at depth. While on these deep-sea expeditions, researchers can passively observe extraordinary, otherworldly life forms in their natural element or selectively collect them to study.

The only way to come close to this experience as a nonscientist — and without a million-dollar submarine — is to dive in the open ocean at night. The deep-sea subjects that appear in shallow water during DVM regularly surprise blackwater divers and scientists. Many divers in this small community of enthusiasts contribute to the academic pursuit of documenting and describing marine life by exchanging information, photographs, and other data. They may even collect specific animals for more detailed DNA profiling.

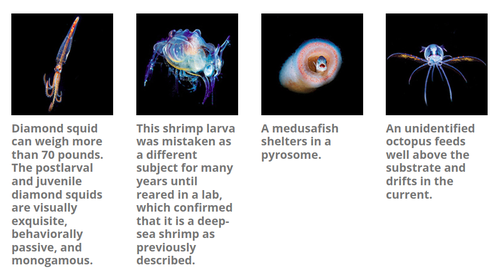

Larval subjects are some of the most intriguing during blackwater dives, where even what would typically be the most common subjects can appear highly exotic. They often sport gaudy elongated spines with muted color patterns or other garish features, which are only outdone by their odd behaviors. You might spot hyperiid amphipods, dragonfish, snaketooth swallowers, deep-sea anglers, stareaters, viperfish, tripod fish, or my all-time favorite — a lovely cusk-eel called the bony-eared assfish. There are monsterlike shrimp, fish with wings, pipefish that resemble dragons, colonies of sea squirts that can reach colossal sizes, and even tiny mollusks that sparkle or resemble drifting leaves. It’s an endless parade of creatures that serve an incredible greater good.

Depending on your location, the ocean depth, predominant current lines, and the moon and tide, any blackwater dive can serve up surprises that will leave divers with even more unanswered questions than before they started. Blackwater dives occur offshore over deep water. Divers remain at recreational depths while drifting over deeper bottom terrain and use a lit downline to help attract plankton.

Drifting over depths in the 600-foot range are a minimum to get a feel for DVM, although there is some deliberation over this point. In Southern California, for example, we discovered that diving closer to shore over 1,200-foot depths to be more productive for larval fish, while we saw more gelatinous plankton while diving over the deeper continental shelf.

Floating over the 600 to 700 feet of water along the Gulf Stream in South Florida is perhaps one of the most astounding blackwater dives. Some of the deepest DVM experiences occur over about 6,000 feet in Kona, Hawai‘i. No matter where you decide to take the plunge, blackwater diving offers firsthand clues to the ocean’s inner workings and how they tie in with humanity and other life on Earth.

“Look small and find big” is a phrase I like to repeat to divers before jumping into the abyss. It’s easy to miss the beauty if you are constantly looking for larger animals. You can find it in how the plankton move and interact. Many of the smaller zooplankton seem to be affectionate toward each other. Sea angels, for instance, embrace when they mate, which is something that I never expected to see in subjects the size of my fingernail.

Squid in the open ocean are also quite different from those inshore or near a reef and are perhaps one of the most interesting groups of sea creatures to encounter. Diverse and fast, they group into schools like a wolfpack or can be solitary. Some of them will pose, creating symmetrical patterns with their arms and tentacles while flushing their photophores into colorful mosaic patterns. Some pelagic octopuses spend their entire lives drifting.

Blackwater diving offers an experience that some call the ultimate fusion of exploring and learning. During the dive you can see some of nature’s best work, and after the dive you can relive your encounters while trying to identify all the creatures. There is one thing that all blackwater divers agree on: It is highly addictive.

Plankton might be small, but they are mighty, and they have a big story to tell. From the shallow surface to the abyssal zone, the greatest show on Earth is going up.

© Alert Diver Magazine Q1 2022/ DAN.org

Larval subjects are some of the most intriguing during blackwater dives, where even what would typically be the most common subjects can appear highly exotic. They often sport gaudy elongated spines with muted color patterns or other garish features, which are only outdone by their odd behaviors. You might spot hyperiid amphipods, dragonfish, snaketooth swallowers, deep-sea anglers, stareaters, viperfish, tripod fish, or my all-time favorite — a lovely cusk-eel called the bony-eared assfish. There are monsterlike shrimp, fish with wings, pipefish that resemble dragons, colonies of sea squirts that can reach colossal sizes, and even tiny mollusks that sparkle or resemble drifting leaves. It’s an endless parade of creatures that serve an incredible greater good.

Depending on your location, the ocean depth, predominant current lines, and the moon and tide, any blackwater dive can serve up surprises that will leave divers with even more unanswered questions than before they started. Blackwater dives occur offshore over deep water. Divers remain at recreational depths while drifting over deeper bottom terrain and use a lit downline to help attract plankton.

Drifting over depths in the 600-foot range are a minimum to get a feel for DVM, although there is some deliberation over this point. In Southern California, for example, we discovered that diving closer to shore over 1,200-foot depths to be more productive for larval fish, while we saw more gelatinous plankton while diving over the deeper continental shelf.

Floating over the 600 to 700 feet of water along the Gulf Stream in South Florida is perhaps one of the most astounding blackwater dives. Some of the deepest DVM experiences occur over about 6,000 feet in Kona, Hawai‘i. No matter where you decide to take the plunge, blackwater diving offers firsthand clues to the ocean’s inner workings and how they tie in with humanity and other life on Earth.

“Look small and find big” is a phrase I like to repeat to divers before jumping into the abyss. It’s easy to miss the beauty if you are constantly looking for larger animals. You can find it in how the plankton move and interact. Many of the smaller zooplankton seem to be affectionate toward each other. Sea angels, for instance, embrace when they mate, which is something that I never expected to see in subjects the size of my fingernail.

Squid in the open ocean are also quite different from those inshore or near a reef and are perhaps one of the most interesting groups of sea creatures to encounter. Diverse and fast, they group into schools like a wolfpack or can be solitary. Some of them will pose, creating symmetrical patterns with their arms and tentacles while flushing their photophores into colorful mosaic patterns. Some pelagic octopuses spend their entire lives drifting.

Blackwater diving offers an experience that some call the ultimate fusion of exploring and learning. During the dive you can see some of nature’s best work, and after the dive you can relive your encounters while trying to identify all the creatures. There is one thing that all blackwater divers agree on: It is highly addictive.

Plankton might be small, but they are mighty, and they have a big story to tell. From the shallow surface to the abyssal zone, the greatest show on Earth is going up.

© Alert Diver Magazine Q1 2022/ DAN.org

Categories

2025

2024

February

March

April

May

October

My name is Rosanne… DAN was there for me?My name is Pam… DAN was there for me?My name is Nadia… DAN was there for me?My name is Morgan… DAN was there for me?My name is Mark… DAN was there for me?My name is Julika… DAN was there for me?My name is James Lewis… DAN was there for me?My name is Jack… DAN was there for me?My name is Mrs. Du Toit… DAN was there for me?My name is Sean… DAN was there for me?My name is Clayton… DAN was there for me?My name is Claire… DAN was there for me?My name is Lauren… DAN was there for me?My name is Amos… DAN was there for me?My name is Kelly… DAN was there for me?Get to Know DAN Instructor: Mauro JijeGet to know DAN Instructor: Sinda da GraçaGet to know DAN Instructor: JP BarnardGet to know DAN instructor: Gregory DriesselGet to know DAN instructor Trainer: Christo van JaarsveldGet to Know DAN Instructor: Beto Vambiane

November

Get to know DAN Instructor: Dylan BowlesGet to know DAN instructor: Ryan CapazorioGet to know DAN Instructor: Tyrone LubbeGet to know DAN Instructor: Caitlyn MonahanScience Saves SharksSafety AngelsDiving Anilao with Adam SokolskiUnderstanding Dive Equipment RegulationsDiving With A PFOUnderwater NavigationFinding My PassionDiving Deep with DSLRDebunking Freediving MythsImmersion Pulmonary OedemaSwimmer's EarMEMBER PROFILE: RAY DALIOAdventure Auntie: Yvette OosthuizenClean Our OceansWhat to Look for in a Dive Boat

2023

January

March

Terrific Freedive ModeKaboom!....The Big Oxygen Safety IssueScuba Nudi ClothingThe Benefits of Being BaldDive into Freedive InstructionCape Marine Research and Diver DevelopmentThe Inhaca Ocean Alliance.“LIGHTS, Film, Action!”Demo DiversSpecial Forces DiverWhat Dive Computers Don\'t Know | PART 2Toughing It Out Is Dangerous

April