Forging a Blue Economy

A group of blacktip reef sharks circles over a shallow coral garden in the Misool Marine Reserve in Raja Ampat, West Papua, Indonesia. Photo by Alex Mustard

CREDITS | Text By Patricia Wuest

For the founders of three of Indonesia’s dive resorts, the mission was clear: Protect the region’s natural resources by providing economic, educational and environmental benefits while empowering residents to participate in the process. These visionaries blazed a path for a “blue economy” — ensuring sustainable use of ocean resources while promoting economic growth and improved livelihoods for the people who live there.

LEMBEH RESORT, NORTH SULAWESI

Sustainable Solutions

“Conservation, sustainability and community are three words that Lembeh Resort has always been passionate about,” said Danny Charlton, co-founder of the resort’s on-site dive center, Critters at Lembeh Resort.

From the beginning, founder Alex Rorimpandey provided training and employment for people living in nearby villages on Lembeh Island. “We encourage villagers to cherish the natural environment, both above and below the sea, as well as their traditional cultures,” Charlton said, adding that the resort staff also have the opportunity to get certified as divers. “We hope it will cultivate a greater appreciation for our unique and precious underwater ecosystems.”

History in the Making

Twenty years ago Rorimpandey, a North Sulawesi native from Tondano, built a single cottage overlooking Lembeh Strait. He intended to build a holiday home for his family, but by December 2002 the property included three guest cottages. Critters at Lembeh Resort began taking guests on dives in the strait.

Rorimpandey also donated materials to build the local church in nearby Pintu Kota Kecil, which laid the groundwork for a strong bond between the resort and the people of Lembeh Island.

Lasting Legacy

Rorimpandey died in July 2003, but his wife and sons retained ownership of the resort and today remain actively involved in its management. The dive operation is managed by Charlton and his wife, Angelique, who is originally from North Sulawesi and is the daughter of the late Dr. Hanny Batuna and his wife, Ineke, who founded Murex Dive Resorts.

“Murex Resort Manado, Murex Bangka and Lembeh Resort have cooperated for almost 18 years, and our staff is like family,” Charlton said. “Many of our staff have been with the company for years — decades in some cases.”

Lembeh Resort provides electrical power for the church and Sunday school, which is at the heart of the community on the island. It also hosts barbecue parties for its guests, during which children from the Sunday school provide musical performances. “Guests can buy a recording from the choir, and proceeds go to the Lembeh Foundation,” Charlton said.

Lembeh Resort guests contribute in other significant ways by bringing school supplies, such as crayons, paper, colored pens, pencils, English dictionaries and books, and sports accessories. “School uniforms are mandatory in Indonesia, and a complete set costs US$55 on average,” Charlton said. “This expense is quite difficult for some families to afford, so we accept donations to help them.”

What’s Next

The nearest village, Pintu Kota Kecil, is populated with small-scale fishers, subsistence farmers and employees of local dive resorts. “Through the Lembeh Foundation, we have constructed a trash bank that people can use to generate income,” Charlton said, “and we are building a learning center with a green library, which we are hoping to complete soon.”

Despite the pandemic, the resort has remained open. “We remain committed to continuing to employ and assist as many people as possible,” Charlton said.

For the founders of three of Indonesia’s dive resorts, the mission was clear: Protect the region’s natural resources by providing economic, educational and environmental benefits while empowering residents to participate in the process. These visionaries blazed a path for a “blue economy” — ensuring sustainable use of ocean resources while promoting economic growth and improved livelihoods for the people who live there.

LEMBEH RESORT, NORTH SULAWESI

Sustainable Solutions

“Conservation, sustainability and community are three words that Lembeh Resort has always been passionate about,” said Danny Charlton, co-founder of the resort’s on-site dive center, Critters at Lembeh Resort.

From the beginning, founder Alex Rorimpandey provided training and employment for people living in nearby villages on Lembeh Island. “We encourage villagers to cherish the natural environment, both above and below the sea, as well as their traditional cultures,” Charlton said, adding that the resort staff also have the opportunity to get certified as divers. “We hope it will cultivate a greater appreciation for our unique and precious underwater ecosystems.”

History in the Making

Twenty years ago Rorimpandey, a North Sulawesi native from Tondano, built a single cottage overlooking Lembeh Strait. He intended to build a holiday home for his family, but by December 2002 the property included three guest cottages. Critters at Lembeh Resort began taking guests on dives in the strait.

Rorimpandey also donated materials to build the local church in nearby Pintu Kota Kecil, which laid the groundwork for a strong bond between the resort and the people of Lembeh Island.

Lasting Legacy

Rorimpandey died in July 2003, but his wife and sons retained ownership of the resort and today remain actively involved in its management. The dive operation is managed by Charlton and his wife, Angelique, who is originally from North Sulawesi and is the daughter of the late Dr. Hanny Batuna and his wife, Ineke, who founded Murex Dive Resorts.

“Murex Resort Manado, Murex Bangka and Lembeh Resort have cooperated for almost 18 years, and our staff is like family,” Charlton said. “Many of our staff have been with the company for years — decades in some cases.”

Lembeh Resort provides electrical power for the church and Sunday school, which is at the heart of the community on the island. It also hosts barbecue parties for its guests, during which children from the Sunday school provide musical performances. “Guests can buy a recording from the choir, and proceeds go to the Lembeh Foundation,” Charlton said.

Lembeh Resort guests contribute in other significant ways by bringing school supplies, such as crayons, paper, colored pens, pencils, English dictionaries and books, and sports accessories. “School uniforms are mandatory in Indonesia, and a complete set costs US$55 on average,” Charlton said. “This expense is quite difficult for some families to afford, so we accept donations to help them.”

What’s Next

The nearest village, Pintu Kota Kecil, is populated with small-scale fishers, subsistence farmers and employees of local dive resorts. “Through the Lembeh Foundation, we have constructed a trash bank that people can use to generate income,” Charlton said, “and we are building a learning center with a green library, which we are hoping to complete soon.”

Despite the pandemic, the resort has remained open. “We remain committed to continuing to employ and assist as many people as possible,” Charlton said.

MISOOL RESORT, RAJA AMPAT

Powerful Partnership

In many ways the founding of Misool Resort is a love story. Soon after meeting, co-founders Andrew and Marit Miners went on a very special third date — a scuba diving trip to Raja Ampat. While there, they explored the remote island of Batbitim and discovered a recently abandoned shark-finning camp. Shocked, they vowed to protect this place with which they had fallen in love.

History in the Making

Building a resort was not in their initial plans. In 2005 Andrew contacted the local clans and asked for permission to create a no-take zone and conservation center. The couple gained the blessing of local tribal leaders and leased an area that has grown to include nine large, uninhabited islands and the rights to the surrounding 460-square-mile seascape. Realizing that a private island resort could fund the conservation work they desperately wanted to do, the couple persuaded investors to share their vision.

Before construction work could begin, however, details of the lease agreement had to be hammered out, said Jo Marlow, marketing and communications manager of Misool Resort. “The boundaries of the leased area came from a series of town hall meetings. The agreement included that the no-take zone should be far enough away from the villages so that their traditional fishing grounds were still available but close enough that artisanal fishers would benefit from the spillover effect of resurging fish populations. The parties agreed on an area that had historically been fished illegally by outside fishermen, including shark-finners.”

On paper it looked good, “but the community lacked the resources and infrastructure to intercept the poachers who were decimating their natural heritage,” Marlow said. A locally staffed ranger patrol was created, and “today the Misool Marine Reserve is a bright beacon of hope.”

Lasting Legacy

In 2019 Misool Resort donated $358,950 to the Misool Foundation, which is enough to operate the ranger patrol. The resort also donates $100 on behalf of every guest and encourages visitors to match the donation. Together the two organizations employ more than 169 staff, 95 percent of whom are Indonesian. “We estimate that these salaries support 650 people from the local community,” Marlow said. “We provide English lessons and job training. We also offer open-water dive training to interested staff from all departments.”

With support from Seacology, the Misool Foundation built a kindergarten in 2011. “Our commitment to education extends to the villages of Yellu and Djabatan,” Marlow said. “We employ seven local teachers, pay their monthly salaries and provide material support to four local schools.”

What’s Next

The resort is committed to reducing its carbon footprint and now gets 60 percent of its energy from renewable sources. It also operates an on-site hydroponic garden, which is expected to produce nearly two tons of organic vegetables in 2021.

“The resort’s mission to protect the world’s richest reefs is meaningless if we do not take immediate and decisive action to reduce our carbon dioxide emissions and their resultant effects on climate change,” Marlow explained. “Our goal is to become carbon neutral by 2025.”

The resort would also like to increase its educational support of local children. “It’s often hard to find teachers who are willing to commit to long-term placements in these remote locations,” Marlow said. “Our education program is a long-term investment in the future of Raja Ampat. We hope that increased access to education will better equip the next generation to take on leadership roles that preserve their natural and cultural heritage.”

* * * * * *

Powerful Partnership

In many ways the founding of Misool Resort is a love story. Soon after meeting, co-founders Andrew and Marit Miners went on a very special third date — a scuba diving trip to Raja Ampat. While there, they explored the remote island of Batbitim and discovered a recently abandoned shark-finning camp. Shocked, they vowed to protect this place with which they had fallen in love.

History in the Making

Building a resort was not in their initial plans. In 2005 Andrew contacted the local clans and asked for permission to create a no-take zone and conservation center. The couple gained the blessing of local tribal leaders and leased an area that has grown to include nine large, uninhabited islands and the rights to the surrounding 460-square-mile seascape. Realizing that a private island resort could fund the conservation work they desperately wanted to do, the couple persuaded investors to share their vision.

Before construction work could begin, however, details of the lease agreement had to be hammered out, said Jo Marlow, marketing and communications manager of Misool Resort. “The boundaries of the leased area came from a series of town hall meetings. The agreement included that the no-take zone should be far enough away from the villages so that their traditional fishing grounds were still available but close enough that artisanal fishers would benefit from the spillover effect of resurging fish populations. The parties agreed on an area that had historically been fished illegally by outside fishermen, including shark-finners.”

On paper it looked good, “but the community lacked the resources and infrastructure to intercept the poachers who were decimating their natural heritage,” Marlow said. A locally staffed ranger patrol was created, and “today the Misool Marine Reserve is a bright beacon of hope.”

Lasting Legacy

In 2019 Misool Resort donated $358,950 to the Misool Foundation, which is enough to operate the ranger patrol. The resort also donates $100 on behalf of every guest and encourages visitors to match the donation. Together the two organizations employ more than 169 staff, 95 percent of whom are Indonesian. “We estimate that these salaries support 650 people from the local community,” Marlow said. “We provide English lessons and job training. We also offer open-water dive training to interested staff from all departments.”

With support from Seacology, the Misool Foundation built a kindergarten in 2011. “Our commitment to education extends to the villages of Yellu and Djabatan,” Marlow said. “We employ seven local teachers, pay their monthly salaries and provide material support to four local schools.”

What’s Next

The resort is committed to reducing its carbon footprint and now gets 60 percent of its energy from renewable sources. It also operates an on-site hydroponic garden, which is expected to produce nearly two tons of organic vegetables in 2021.

“The resort’s mission to protect the world’s richest reefs is meaningless if we do not take immediate and decisive action to reduce our carbon dioxide emissions and their resultant effects on climate change,” Marlow explained. “Our goal is to become carbon neutral by 2025.”

The resort would also like to increase its educational support of local children. “It’s often hard to find teachers who are willing to commit to long-term placements in these remote locations,” Marlow said. “Our education program is a long-term investment in the future of Raja Ampat. We hope that increased access to education will better equip the next generation to take on leadership roles that preserve their natural and cultural heritage.”

* * * * * *

Wakatobi often recruits and trains divemasters from the local village.

WAKATOBI DIVE RESORT, SOUTHEAST SULAWESI

Collaborative Community

“Wakatobi Resort is surrounded by some of the most pristine and best-protected reef systems in the world,” said Karen Stearns, director of marketing and media relations for the resort. “In addition to preserving the region’s high biodiversity, the resort’s groundbreaking collaborative conservation program has become a model for sustainable ecotourism.”

History in the Making

Before founder Lorenz Mäder opened the southeastern Sulawesi resort in 1995, he met with local fishers and village elders from surrounding communities and offered a unique proposal. In exchange for agreeing to honor a no-take zone on nearly 4 miles of reef, the residents of 17 area villages would receive direct lease payments from Wakatobi. Since then, the initial no-take zone has expanded to cover more than 12 miles of reef and is now one of the world’s largest privately funded marine protected areas.

“These zones replenish fish populations by serving as safe breeding grounds, which in turn boosts sustainable harvests in areas outside the reserve,” Stearns said. “The same fishermen who were initially skeptical of the program are now some of its most vigilant enforcers.”

History in the Making

Before founder Lorenz Mäder opened the southeastern Sulawesi resort in 1995, he met with local fishers and village elders from surrounding communities and offered a unique proposal. In exchange for agreeing to honor a no-take zone on nearly 4 miles of reef, the residents of 17 area villages would receive direct lease payments from Wakatobi. Since then, the initial no-take zone has expanded to cover more than 12 miles of reef and is now one of the world’s largest privately funded marine protected areas.

“These zones replenish fish populations by serving as safe breeding grounds, which in turn boosts sustainable harvests in areas outside the reserve,” Stearns said. “The same fishermen who were initially skeptical of the program are now some of its most vigilant enforcers.”

What’s Next

Wakatobi’s legacy to the community is sustainable fisheries and economic prosperity. “The resort has continued its monthly compensation payments to local villages, even during the pandemic when we’ve had no guests,” Stearns said. “Those who visit here can witness how positive change can be economically beneficial as well and share our founder’s vision of creating benefit for all parties. Tourists learn to appreciate a living reef and understand what has been lost in other places. They contribute by visiting and spreading the word to others. Seeing the difference they make motivates others to actively protect reefs around the globe.”

* * * * * *

Collaborative Community

“Wakatobi Resort is surrounded by some of the most pristine and best-protected reef systems in the world,” said Karen Stearns, director of marketing and media relations for the resort. “In addition to preserving the region’s high biodiversity, the resort’s groundbreaking collaborative conservation program has become a model for sustainable ecotourism.”

History in the Making

Before founder Lorenz Mäder opened the southeastern Sulawesi resort in 1995, he met with local fishers and village elders from surrounding communities and offered a unique proposal. In exchange for agreeing to honor a no-take zone on nearly 4 miles of reef, the residents of 17 area villages would receive direct lease payments from Wakatobi. Since then, the initial no-take zone has expanded to cover more than 12 miles of reef and is now one of the world’s largest privately funded marine protected areas.

“These zones replenish fish populations by serving as safe breeding grounds, which in turn boosts sustainable harvests in areas outside the reserve,” Stearns said. “The same fishermen who were initially skeptical of the program are now some of its most vigilant enforcers.”

History in the Making

Before founder Lorenz Mäder opened the southeastern Sulawesi resort in 1995, he met with local fishers and village elders from surrounding communities and offered a unique proposal. In exchange for agreeing to honor a no-take zone on nearly 4 miles of reef, the residents of 17 area villages would receive direct lease payments from Wakatobi. Since then, the initial no-take zone has expanded to cover more than 12 miles of reef and is now one of the world’s largest privately funded marine protected areas.

“These zones replenish fish populations by serving as safe breeding grounds, which in turn boosts sustainable harvests in areas outside the reserve,” Stearns said. “The same fishermen who were initially skeptical of the program are now some of its most vigilant enforcers.”

What’s Next

Wakatobi’s legacy to the community is sustainable fisheries and economic prosperity. “The resort has continued its monthly compensation payments to local villages, even during the pandemic when we’ve had no guests,” Stearns said. “Those who visit here can witness how positive change can be economically beneficial as well and share our founder’s vision of creating benefit for all parties. Tourists learn to appreciate a living reef and understand what has been lost in other places. They contribute by visiting and spreading the word to others. Seeing the difference they make motivates others to actively protect reefs around the globe.”

* * * * * *

Bilikiki works closely with the villages along their cruise itinerary to buy local produce to help sustain their economies.

BILIKIKI LIVEABOARD, SOLOMON ISLANDS

Land-based resorts are not the only entities that work with villagers to provide economic incentives for protecting local resources. The Bilikiki liveaboard has been operating since 1998 in another Coral Triangle hot spot, the Solomon Islands. Traditionally, the local tribe owns all land and adjoining reefs and the tribe’s chief controls them. Since the beginning, the company that owns Bilikiki has paid to dive on the reefs it visits. Those payments have prompted the local tribal chiefs to protect their reefs.

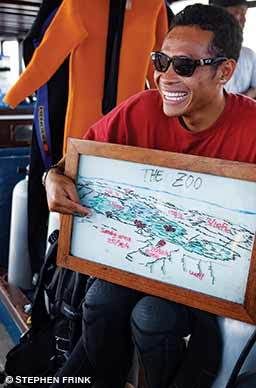

The Bilikiki itinerary includes a visit to Marovo Lagoon, where local villagers produce exquisite wood carvings that guests can purchase. Since its first cruise, the company has handed out seeds and then paid for the produce grown by local villagers, who deliver fresh vegetables and fruits to Bilikiki using traditional canoes.

“There are remote areas where people rely mostly on growing crops and catching fish, so to be able to introduce some small form of mutually beneficial economy is helpful to everyone,” said Sam Leeson, managing director of Bilikiki Cruises. “It makes the local people as happy to have us around as we are to be there.”

Land-based resorts are not the only entities that work with villagers to provide economic incentives for protecting local resources. The Bilikiki liveaboard has been operating since 1998 in another Coral Triangle hot spot, the Solomon Islands. Traditionally, the local tribe owns all land and adjoining reefs and the tribe’s chief controls them. Since the beginning, the company that owns Bilikiki has paid to dive on the reefs it visits. Those payments have prompted the local tribal chiefs to protect their reefs.

The Bilikiki itinerary includes a visit to Marovo Lagoon, where local villagers produce exquisite wood carvings that guests can purchase. Since its first cruise, the company has handed out seeds and then paid for the produce grown by local villagers, who deliver fresh vegetables and fruits to Bilikiki using traditional canoes.

“There are remote areas where people rely mostly on growing crops and catching fish, so to be able to introduce some small form of mutually beneficial economy is helpful to everyone,” said Sam Leeson, managing director of Bilikiki Cruises. “It makes the local people as happy to have us around as we are to be there.”

Bilikiki partners with the Loloma Foundation to provide dental and vision care to local Solomon Islanders.

A Helping Hand

The three resorts accept donations to fund their conservation work and community initiatives. Here’s how to help:

The three resorts accept donations to fund their conservation work and community initiatives. Here’s how to help:

- Lembeh Foundation, lembehfoundation.org

The Lembeh Foundation accepts general donations, but you can also designate your contribution for local schools, households and families or resort staff. - Misool Foundation, misoolfoundation.org

The Misool Foundation uses funds to benefit its recycling program and support the Misool Ranger Patrol. - Wakatobi Collaborative Reef Conservation Program, office@wakatobi.com

Donations help provide the local population with a sustainable source of regular lease disbursements.

Categories

2025

2024

February

March

April

May

October

My name is Rosanne… DAN was there for me?My name is Pam… DAN was there for me?My name is Nadia… DAN was there for me?My name is Morgan… DAN was there for me?My name is Mark… DAN was there for me?My name is Julika… DAN was there for me?My name is James Lewis… DAN was there for me?My name is Jack… DAN was there for me?My name is Mrs. Du Toit… DAN was there for me?My name is Sean… DAN was there for me?My name is Clayton… DAN was there for me?My name is Claire… DAN was there for me?My name is Lauren… DAN was there for me?My name is Amos… DAN was there for me?My name is Kelly… DAN was there for me?Get to Know DAN Instructor: Mauro JijeGet to know DAN Instructor: Sinda da GraçaGet to know DAN Instructor: JP BarnardGet to know DAN instructor: Gregory DriesselGet to know DAN instructor Trainer: Christo van JaarsveldGet to Know DAN Instructor: Beto Vambiane

November

Get to know DAN Instructor: Dylan BowlesGet to know DAN instructor: Ryan CapazorioGet to know DAN Instructor: Tyrone LubbeGet to know DAN Instructor: Caitlyn MonahanScience Saves SharksSafety AngelsDiving Anilao with Adam SokolskiUnderstanding Dive Equipment RegulationsDiving With A PFOUnderwater NavigationFinding My PassionDiving Deep with DSLRDebunking Freediving MythsImmersion Pulmonary OedemaSwimmer's EarMEMBER PROFILE: RAY DALIOAdventure Auntie: Yvette OosthuizenClean Our OceansWhat to Look for in a Dive Boat

2023

January

March

Terrific Freedive ModeKaboom!....The Big Oxygen Safety IssueScuba Nudi ClothingThe Benefits of Being BaldDive into Freedive InstructionCape Marine Research and Diver DevelopmentThe Inhaca Ocean Alliance.“LIGHTS, Film, Action!”Demo DiversSpecial Forces DiverWhat Dive Computers Don\'t Know | PART 2Toughing It Out Is Dangerous

April