Conservation Photography

The Power to change the World

Text And Photos by Paul Hilton

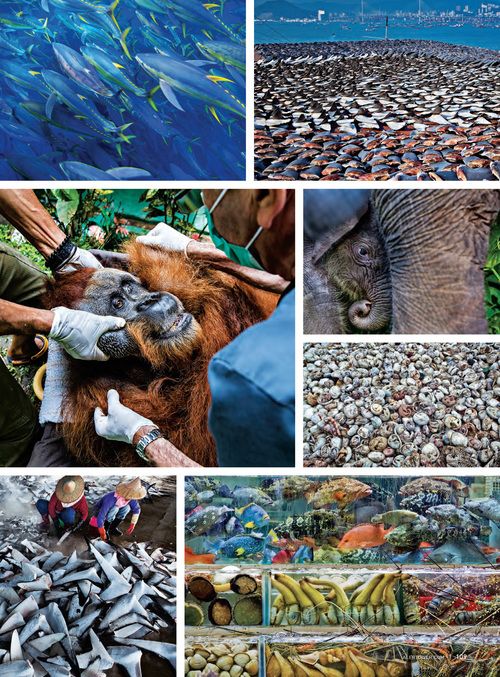

As a conservation photographer, I am a professional observer. I love my line of work and consider myself privileged to have it, but for all its rewards it has some drawbacks. One of the overriding truths I’ve observed is that so many people still see our resources as commodities rather than as things we need to value and preserve. Sadly, the wrong questions are still being asked, particularly at the corporate level: How much timber would that forest provide? How many tons of tuna can be caught in a single net? How much are we legally allowed to trade? Considering the black market in wildlife, humans appear to be at greed-fueled war with their own ecological support system.

Every dollar we spend is an opportunity to vote for either a more sustainable future or the destruction of the planet. That idea may sound far-fetched, but my experience in this field has showed me that every day is an opportunity to create change. I also believe that a photograph has the power to bridge languages and cultural divides and resonate with people in all walks of life. Images have the potential to spark conversations that change our world, but photographers must get down in the trenches on the frontlines of conservation, where it’s frequently uncomfortable and sometimes just plain terrifying, especially when covering issues that are cruel as well as legally and morally wrong.

My philosophy when approaching a subject is to beg for forgiveness, if necessary, rather than ask for permission. Sometimes you have only minutes or just seconds to create an image that is balanced and pleasing to the eye and has the depth to become timeless. I want to make people stop and look even if the subject is dark or confrontational. Only when we confront these issues head-on will solutions follow.

My main advice to anyone entering this profession is to always thoroughly do your homework. Research your subject as much as possible, talk to experts, and win the trust of locals. Merely getting to be in a situation where everything lines up for the award-winning shot can sometimes take years, so your motivation can’t be only to create incredible images. You must really care. It’s a marathon that you may never finish — change happens slowly. Conservation photography takes passion and a lifetime of dedication.

This life is not for the faint-hearted, but in a time of so much destruction we need all the help we can get to highlight the atrocities affecting the natural world. The camera is our weapon. Without many of these images, their stories would never hit the mainstream media, leaving the world blind to the facts. The planet belongs to all of us, and it’s our responsibility to protect it.

That ethos was particularly apparent to me during my 10 years documenting the global shark fin trade from the coast of Mozambique to the dining tables of Hong Kong. It was only after years of following the industry that I started to see a pattern in the modus operandi of a conservation photographer. While uncovering huge drying facilities, where tens of thousands of fins dry on rooftops or in warehouses, behind walls and out of sight, I had a few minutes or less to create an image that would speak volumes. I had to show scale and cruelty, evoke an emotional response and send a message to the world. If I could do all that in one image, in one moment, I had succeeded.

Over the years I’ve covered many poignant issues: bear bile farming, the manta ray trade, palm oil production, forest destruction, overfishing, pangolin poaching and now the live reef fish trade, which is exploiting some of the most biodiverse coral reefs on the planet. Dynamite and cyanide fishing are rampant within the reef fish industry, which is valued at more than a billion dollars annually in Hong Kong alone. Reef fish are being transported from countries without any quotas or policing of any kind.

In 2009 I worked with Greenpeace on a tuna campaign, tracking illegal fishing vessels across the Pacific Ocean. My assignment as the onboard photographer put me on helicopters and high-speed pursuits in inflatable boats looking for illegal fishing vessels. One flight especially stands out. Our team was looking for fishing vessels in the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) in specific countries to identify who had licenses and who didn’t. After spotting a boat, we’d get into position for me to photograph the bow, stern and call sign to help with identification. We came across a Japanese longliner fishing on the border area of the Cook Islands EEZ and international waters. It was obvious that the crew had longlines in the water, some stretching for 100 miles, with more than 3,000 hooks on just one line. After we confirmed they did not have a license to fish in the waters of the Cook Islands, our pilot moved us into a holding position just behind a cloud and waited.

After 30 minutes the crew finally started to haul their lines on deck as the vessel moved deeper into Cook Island territory. Our fuel was getting low, and we realized something needed to happen soon. At that point I said urgently to the pilot, “Go, go, go!” Within seconds we were hovering directly above the deck, and I was photographing a 130- to 150-pound yellowfin tuna being dragged on board. At the same time I had to position my handheld GPS on the left side of my frame to get the coordinates for the image to stand up in court. I used two cameras: one with a wide-angle lens and one with a long 300mm lens to get all the details.

I soon found myself in a courtroom on Rarotonga listening to the verdict. Japanese fisheries were found guilty for fishing in the EEZ without a license and were ordered to pay the Cook Islands government NZ$1.5 million in fines. That was a good day at the office and why I go to sea.

For the past eight years I have spent a large part of my time in the Leuser Ecosystem in Sumatra, Indonesia. This huge tropical forest is the last place on earth where tigers, rhinos, orangutans and elephants still run wild together, but it is under immense pressure. The problems facing the ecosystem are complicated and include illegal logging, palm oil expansion, hydroelectric dams, road construction and community encroachment. Over time I’ve highlighted all these issues, capturing both the tragic destruction and the stunning beauty of the area to give the viewer a broad understanding of the complexities at play. Most of the problems stem from our buying habits as consumers. As WildAid asserts, “When the buying stops, the killing can too.”

Conservation photography has given me a chance to see the planet’s most majestic beings in their own habitats: the world’s forests, coral reefs and open expanses of ocean. But witnessing the careless depravity humans can bring upon our environment can present a level of darkness to those documenting it; the risk is letting it get to you. It’s important to instill balance, check in with yourself and spend time in pristine nature while maintaining solid relationships — maybe even throw in some meditation.

My final bit of guidance is to associate yourself with universities, nongovernmental organizations, scientists, conservationists, fellow photographers and media outlets. Prioritize your networks. Relationships take time; eventually your connections will start to link up and create amazing opportunities across the globe.

Now is the time to care. Now is the time to act. What we are doing to our oceans and forests is a crime against nature and is based on the belief that money and profits should outweigh all other considerations, including the survival of irreplaceable species and ecosystems.

Now grab your camera and shine a light. The world needs to see your message. AD

Text And Photos by Paul Hilton

As a conservation photographer, I am a professional observer. I love my line of work and consider myself privileged to have it, but for all its rewards it has some drawbacks. One of the overriding truths I’ve observed is that so many people still see our resources as commodities rather than as things we need to value and preserve. Sadly, the wrong questions are still being asked, particularly at the corporate level: How much timber would that forest provide? How many tons of tuna can be caught in a single net? How much are we legally allowed to trade? Considering the black market in wildlife, humans appear to be at greed-fueled war with their own ecological support system.

Every dollar we spend is an opportunity to vote for either a more sustainable future or the destruction of the planet. That idea may sound far-fetched, but my experience in this field has showed me that every day is an opportunity to create change. I also believe that a photograph has the power to bridge languages and cultural divides and resonate with people in all walks of life. Images have the potential to spark conversations that change our world, but photographers must get down in the trenches on the frontlines of conservation, where it’s frequently uncomfortable and sometimes just plain terrifying, especially when covering issues that are cruel as well as legally and morally wrong.

My philosophy when approaching a subject is to beg for forgiveness, if necessary, rather than ask for permission. Sometimes you have only minutes or just seconds to create an image that is balanced and pleasing to the eye and has the depth to become timeless. I want to make people stop and look even if the subject is dark or confrontational. Only when we confront these issues head-on will solutions follow.

My main advice to anyone entering this profession is to always thoroughly do your homework. Research your subject as much as possible, talk to experts, and win the trust of locals. Merely getting to be in a situation where everything lines up for the award-winning shot can sometimes take years, so your motivation can’t be only to create incredible images. You must really care. It’s a marathon that you may never finish — change happens slowly. Conservation photography takes passion and a lifetime of dedication.

This life is not for the faint-hearted, but in a time of so much destruction we need all the help we can get to highlight the atrocities affecting the natural world. The camera is our weapon. Without many of these images, their stories would never hit the mainstream media, leaving the world blind to the facts. The planet belongs to all of us, and it’s our responsibility to protect it.

That ethos was particularly apparent to me during my 10 years documenting the global shark fin trade from the coast of Mozambique to the dining tables of Hong Kong. It was only after years of following the industry that I started to see a pattern in the modus operandi of a conservation photographer. While uncovering huge drying facilities, where tens of thousands of fins dry on rooftops or in warehouses, behind walls and out of sight, I had a few minutes or less to create an image that would speak volumes. I had to show scale and cruelty, evoke an emotional response and send a message to the world. If I could do all that in one image, in one moment, I had succeeded.

Over the years I’ve covered many poignant issues: bear bile farming, the manta ray trade, palm oil production, forest destruction, overfishing, pangolin poaching and now the live reef fish trade, which is exploiting some of the most biodiverse coral reefs on the planet. Dynamite and cyanide fishing are rampant within the reef fish industry, which is valued at more than a billion dollars annually in Hong Kong alone. Reef fish are being transported from countries without any quotas or policing of any kind.

In 2009 I worked with Greenpeace on a tuna campaign, tracking illegal fishing vessels across the Pacific Ocean. My assignment as the onboard photographer put me on helicopters and high-speed pursuits in inflatable boats looking for illegal fishing vessels. One flight especially stands out. Our team was looking for fishing vessels in the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) in specific countries to identify who had licenses and who didn’t. After spotting a boat, we’d get into position for me to photograph the bow, stern and call sign to help with identification. We came across a Japanese longliner fishing on the border area of the Cook Islands EEZ and international waters. It was obvious that the crew had longlines in the water, some stretching for 100 miles, with more than 3,000 hooks on just one line. After we confirmed they did not have a license to fish in the waters of the Cook Islands, our pilot moved us into a holding position just behind a cloud and waited.

After 30 minutes the crew finally started to haul their lines on deck as the vessel moved deeper into Cook Island territory. Our fuel was getting low, and we realized something needed to happen soon. At that point I said urgently to the pilot, “Go, go, go!” Within seconds we were hovering directly above the deck, and I was photographing a 130- to 150-pound yellowfin tuna being dragged on board. At the same time I had to position my handheld GPS on the left side of my frame to get the coordinates for the image to stand up in court. I used two cameras: one with a wide-angle lens and one with a long 300mm lens to get all the details.

I soon found myself in a courtroom on Rarotonga listening to the verdict. Japanese fisheries were found guilty for fishing in the EEZ without a license and were ordered to pay the Cook Islands government NZ$1.5 million in fines. That was a good day at the office and why I go to sea.

For the past eight years I have spent a large part of my time in the Leuser Ecosystem in Sumatra, Indonesia. This huge tropical forest is the last place on earth where tigers, rhinos, orangutans and elephants still run wild together, but it is under immense pressure. The problems facing the ecosystem are complicated and include illegal logging, palm oil expansion, hydroelectric dams, road construction and community encroachment. Over time I’ve highlighted all these issues, capturing both the tragic destruction and the stunning beauty of the area to give the viewer a broad understanding of the complexities at play. Most of the problems stem from our buying habits as consumers. As WildAid asserts, “When the buying stops, the killing can too.”

Conservation photography has given me a chance to see the planet’s most majestic beings in their own habitats: the world’s forests, coral reefs and open expanses of ocean. But witnessing the careless depravity humans can bring upon our environment can present a level of darkness to those documenting it; the risk is letting it get to you. It’s important to instill balance, check in with yourself and spend time in pristine nature while maintaining solid relationships — maybe even throw in some meditation.

My final bit of guidance is to associate yourself with universities, nongovernmental organizations, scientists, conservationists, fellow photographers and media outlets. Prioritize your networks. Relationships take time; eventually your connections will start to link up and create amazing opportunities across the globe.

Now is the time to care. Now is the time to act. What we are doing to our oceans and forests is a crime against nature and is based on the belief that money and profits should outweigh all other considerations, including the survival of irreplaceable species and ecosystems.

Now grab your camera and shine a light. The world needs to see your message. AD

Posted in Alert Diver Winter Editions

Posted in Conservation, Photography, alert diver, Dive safety, Humans

Posted in Conservation, Photography, alert diver, Dive safety, Humans

Categories

2025

2024

February

March

April

May

October

My name is Rosanne… DAN was there for me?My name is Pam… DAN was there for me?My name is Nadia… DAN was there for me?My name is Morgan… DAN was there for me?My name is Mark… DAN was there for me?My name is Julika… DAN was there for me?My name is James Lewis… DAN was there for me?My name is Jack… DAN was there for me?My name is Mrs. Du Toit… DAN was there for me?My name is Sean… DAN was there for me?My name is Clayton… DAN was there for me?My name is Claire… DAN was there for me?My name is Lauren… DAN was there for me?My name is Amos… DAN was there for me?My name is Kelly… DAN was there for me?Get to Know DAN Instructor: Mauro JijeGet to know DAN Instructor: Sinda da GraçaGet to know DAN Instructor: JP BarnardGet to know DAN instructor: Gregory DriesselGet to know DAN instructor Trainer: Christo van JaarsveldGet to Know DAN Instructor: Beto Vambiane

November

Get to know DAN Instructor: Dylan BowlesGet to know DAN instructor: Ryan CapazorioGet to know DAN Instructor: Tyrone LubbeGet to know DAN Instructor: Caitlyn MonahanScience Saves SharksSafety AngelsDiving Anilao with Adam SokolskiUnderstanding Dive Equipment RegulationsDiving With A PFOUnderwater NavigationFinding My PassionDiving Deep with DSLRDebunking Freediving MythsImmersion Pulmonary OedemaSwimmer's EarMEMBER PROFILE: RAY DALIOAdventure Auntie: Yvette OosthuizenClean Our OceansWhat to Look for in a Dive Boat

2023

January

March

Terrific Freedive ModeKaboom!....The Big Oxygen Safety IssueScuba Nudi ClothingThe Benefits of Being BaldDive into Freedive InstructionCape Marine Research and Diver DevelopmentThe Inhaca Ocean Alliance.“LIGHTS, Film, Action!”Demo DiversSpecial Forces DiverWhat Dive Computers Don\'t Know | PART 2Toughing It Out Is Dangerous

April